A Poem a Week #2

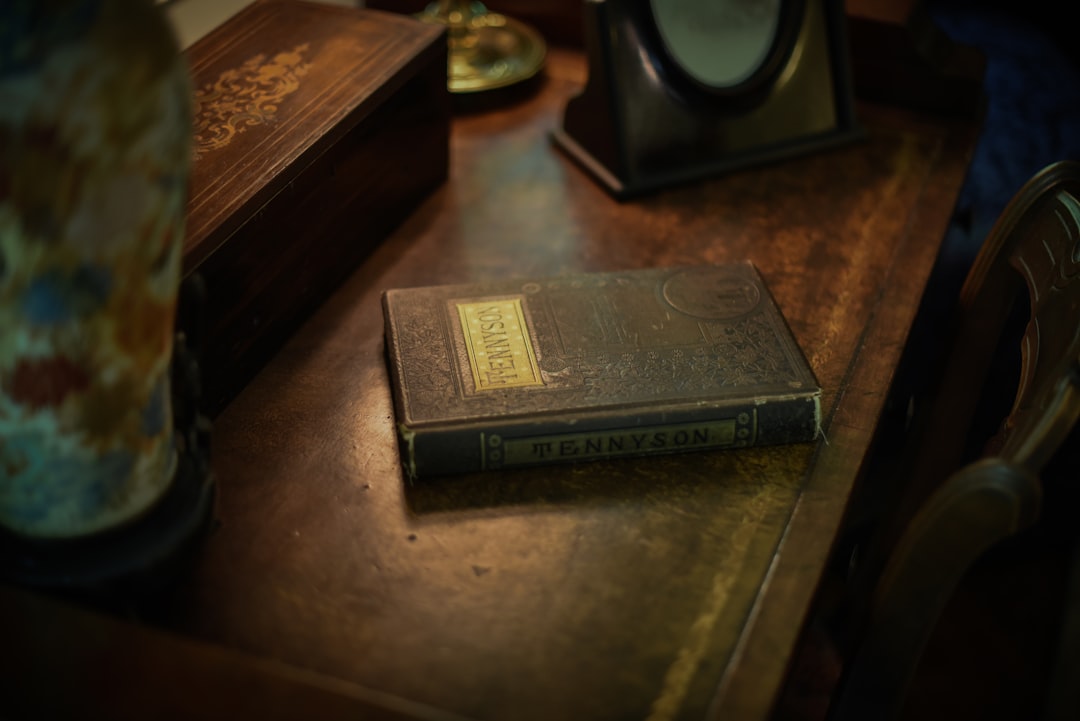

Alfred Tennyson's "Ulysses"

Ulysses (Odysseus in ancient Greek) has been a part of our literary world since Homer’s Odyssey and carried forward into Dante’s Inferno and Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, among others. Even in our modern world we meet Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses, who is the modern day version. Alfred Tennyson’s “Ulysses” is a graceful reading, yet we are still filled with the same questions as to what kind of hero Ulysses really is.

Tennyson wrote this poem shortly after the death of his closest friend, Arthur Henry Hallam. What we can gather is not just a take on the extraordinarily complex nature of Ulysses, Tennyson’s writing is also an elegy—a lot of his best poetry happens to be elegies—and simultaneously pushes the reader to acceptance of life’s hardships and strive forward. But not before Ulysses’ contradictory monologue starts us on a journey through his own self-importance and malaise. The opening of “Ulysses” paints a bleak picture of life as the king of Ithaca:

It little profits that an idle king,

By this still hearth, among these barren crags,

Match'd with an aged wife, I mete and dole

Unequal laws unto a savage race,

That hoard, and sleep, and feed, and know not me.

These first five lines are beautifully written and provide a deep view into his own discontent with life that is his experience: the Ithacans who “know not me.” An aging Penelope, who he leaves at any chance for adventure. And finally the desire to “mete and dole / Unequal laws” without what seems to be any desire to improve them. (Sounds like a world at least most of us are familiar with.) The hero’s fixation on his own restlessness and boredom is a powerful image and one that I think is particularly relatable to men as they age where regret festers. As Ulysses continues with his monologue, there are still layers to uncover, no matter the judgments we might make.

I cannot rest from travel: I will drink

Life to the lees: All times I have enjoy'd

Greatly, have suffer'd greatly, both with those

That loved me, and alone, on shore, and when

Thro' scudding drifts the rainy Hyades

Vext the dim sea: I am become a name;

For always roaming with a hungry heart

Much have I seen and known; cities of men

And manners, climates, councils, governments,

Myself not least, but honour'd of them all;

And drunk delight of battle with my peers,

Far on the ringing plains of windy Troy.

I am a part of all that I have met;

Yet all experience is an arch wherethro'

Gleams that untravell'd world whose margin fades

For ever and forever when I move.

How dull it is to pause, to make an end,

To rust unburnish'd, not to shine in use!

As tho' to breathe were life! Life piled on life

Were all too little, and of one to me

Little remains: but every hour is saved

From that eternal silence, something more,

A bringer of new things; and vile it were

For some three suns to store and hoard myself,

And this gray spirit yearning in desire

To follow knowledge like a sinking star,

Beyond the utmost bound of human thought.

One thing we love about literary characters is our self-identification with heroes. This is handed to us on a silver platter to grasp here. With any literary version of Ulysses we might read, this is generally the case. “I am become a name / For always roaming with a hungry heart / Much have I seen and known,” feels like it is piercing the reader with self-importance, but it also feels expected from the Ulysses we know. What follows paints a more complex picture than an egoistical hero.

“I am part of all that I have met” is really an interesting line given to us by the quester. Emphasizing the double “I” will bring out the egoist, but it is really the quester telling the tale and the “all” emphasizes how experience and his voyages have shaped him. We see this play out through the rest of this stanza as we see Ulysses attempting to fight off old age. “As tho’ to breathe were life!” is a firm rejection of old age begetting wisdom and stillness. Now moving forward into a final voyage for Ulysses.

This is my son, mine own Telemachus,

To whom I leave the sceptre and the isle,—

Well-loved of me, discerning to fulfil

This labour, by slow prudence to make mild

A rugged people, and thro' soft degrees

Subdue them to the useful and the good.

Most blameless is he, centred in the sphere

Of common duties, decent not to fail

In offices of tenderness, and pay

Meet adoration to my household gods,

When I am gone. He works his work, I mine.

The penultimate stanza is rather unconvincing of his love for Telemachus. His son’s virtue is something he shuns. It feels like a sour projection of his own inability to enjoy stillness. “He works his work, I mine” is the proverbial nail in the coffin of what contents him to “leave the sceptre and the isle” to his son and sends him on his final voyage. This is actually comfort to the reader.

There lies the port; the vessel puffs her sail:

There gloom the dark, broad seas. My mariners,

Souls that have toil'd, and wrought, and thought with me—

That ever with a frolic welcome took

The thunder and the sunshine, and opposed

Free hearts, free foreheads—you and I are old;

Old age hath yet his honour and his toil;

Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note, may yet be done,

Not unbecoming men that strove with Gods.

The lights begin to twinkle from the rocks:

The long day wanes: the slow moon climbs: the deep

Moans round with many voices. Come, my friends,

'T is not too late to seek a newer world.

Push off, and sitting well in order smite

The sounding furrows; for my purpose holds

To sail beyond the sunset, and the baths

Of all the western stars, until I die.

It may be that the gulfs will wash us down:

It may be we shall touch the Happy Isles,

And see the great Achilles, whom we knew.

Tho' much is taken, much abides; and tho'

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

The final stanza clearly expresses the most loving gaze from Ulysses. “Death closes all” is not only Ulysses’ forecast of how this final voyage will end and who he would rather die with, but an expression of Tennyson’s grief for his friend. The final line, “To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield,” reflects Milton’s Satan in Paradise Lost, “And courage never to submit or yield / And what is else not to be overcome?” While we may have our own conflicting views of Ulysses and his heroism, Tennyson’s writing is unmistakably extraordinary.

Great poetry is not something we should take for granted as there are profound lessons to be learned and a beautiful way for us to communicate it to ourselves. As Harold Bloom writes in How to Read and Why, “Poems can help us to speak to ourselves more clearly and more fully, and to overhear that speaking… We speak to an otherness in ourselves, or to what may be best and oldest in ourselves. We read to find ourselves, more fully and more strange than otherwise we could hope to find.” Being content with solitude and stillness are in fact great lessons to be learned from “Ulysses” and is there a better form of living to speak to ourself and find our own full, strange self?

As always, I appreciate you taking the time to read. If you have been forwarded this or have randomly stumbled across it, please feel free to subscribe below.